What I learned from the 18xx System

For those of you not familiar with my favorite past time I will give you a brief overview. I love board games, specifically one system called 18xx. I fell in love with the 18xx group of games TEN years ago when I was introduced to a very bland looking game called 1870. What the game lacked in aesthetics it made up in game play. The mechanics of the game are simple. Invest in shares of companies that make YOU money, avoid bad investments and at the end of the game, manage your portfolio well enough and have the most personal cash! But the destination from point A to point B is not always clear cut.

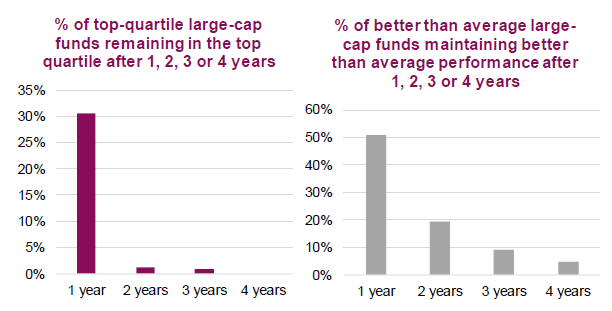

Which brings me to my point. Being a disciplined investor isn’t always easy. Most investors operate within the powerful grip of outcome bias; where they assume that good results must be the consequence of skill and will persist, and that poor results are a prelude to ongoing disappointment. This leads to the damaging behavior of performance chasing, where we sell our holdings in laggard funds and reinvest in recent winners. History is only a guide, past performance is not an accurate predictor of future performance.

Performance chasing then, isn’t a goal nor is it, in and of itself, a financial plan. There is no accurate predictor nor indicator of future performance and it becomes nothing more than a moving target. A target that is very difficult to hit consistently. Performance chasing, undermines an investor’s portfolio by diminishing long term returns.

Consistency, rationality and discipline

A game of 18xx, as with investment planning, requires discipline, rationality and control of your emotional biases.

Why did I feel compelled to sell off shares that I knew were profitable and were from a company that was directed by a player I knew had a good run and was making money? Why did I short a strong company, bail out of my position for a quick payout and usher in, disastrous long term consequences for my portfolio?

I could come up with a lot of reasons, excuses and justifications, but the short answer is; I did it because I got scared that things “might go bad” without any factual evidence to back up my paranoia and that’s not a very good reason to do anything.

One of the things that I love most about 18xx, is the almost limitless possibilities of choice. It’s the same with all the available options for investments. Operationally, I know the sequence and how to play the game. But while the moves themselves may be sequentially simple, the rationale behind them can be impossibly complex. Where do I want to go? What are my opponents trying to accomplish for themselves? How do I keep the most options open for me while trying to block them out?

In comparison, investors ask similar questions. What’s the best investment option? How do I maximize my return and minimize my risk? What about global warming? The war in Iran? Russia? How do these forces play a role in my decision? But are these questions necessarily good? Or are they simply a manifestation of outcome bias or worse, a form of avoidance behavior?

What do you mean I have to save to retire? But I want it now!

Look, I get it. Life is challenging at best, brutal at worst. It doesn’t get better, unless you start planning right away. What does that mean? It means being honest with yourself, asking the HARD questions. Was it the rate of return that brought your portfolio down? Or did you sell at the worst possible moment? Go on that trip you couldn’t really afford, but did anyway? Squandering your retirement resources to pay for it, setting yourself back. Just like I sold shares I shouldn’t have sold, bought that big shiny train that wasn’t really necessary but looked SO good! I played the game foolishly and came in SECOND LAST. I can’t blame anyone but myself. I played badly. I made impulsive, rash decisions, without thinking about the long term affect on my game. I ended up where I should be.

A financial plan needs to be based on an achievable, realistic goal. Looking for the best rate of return, is not a goal. Without a written financial plan in place that keeps us accountable, or a strategy we can turn too, we tend to veer off course. The worst thing that can happen to your investment portfolio is impulsive, gut reactions, manipulated by outside forces that have no bearing on the quality or performance of your investments. Jumping ship before you reach your destination so to speak. How funds performed in the past year plays a much greater role in investment selection than it should and needs to be avoided.